The American Dream: How I got the opportunity to choose

The American dream symbolizes the United States’ national philosophy. It encapsulates a set of ideals that include opportunities for prosperity and success. The nation demands democracy, rights, freedom, economic opportunity, and equality. In 1931, James Truslow Adams conceived this idea of the American Dream. He envisioned a "dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement" (Epic of America). Though many people disagree on what defines the ideals, this word resonates with America's imagination very strongly.

It proved so influential that Xinhua has started promoting his "The Chinese Dream." In the Chinese Lunar New Year Reception in January 2020, President Xi noted that achieving the first centenary goal of securing "a decisive victory in building a moderately prosperous society in all respects and fighting poverty" is a milestone in the process of realizing the "Chinese Dream" of national rejuvenation (Source: Xinhua).

So, we know the American Dream is so powerful it has been transformed to be used in an entirely different country with a starkly contrasting political system. But, what do we not know about the American Dream? What does the projected mobility look like? What constitutes richer and fuller? And can anyone attain it? Women? Minorities? How does education affect mobility? What is the current generation’s outlook? Is it still singular or more collective?

I grew up in a household where the American Dream was heavily pursued. My father has told me countless stories of how growing up in India and how he built his concept of the American Dream from watching TV. His uncle who lived in America had bought my father's family their first TV. As he watched the technological advances during the Cold War (1962-1979), he made it his goal to start his own business and provide certain liberties for his family that he could not in India, such as the freedom to choose what you want to do. In 1993, my parents received the opportunity to do so. My mother came to the U.S. to present her findings from her Ph.D. dissertation at a conference organized by The American Chemical Society.

Though my father was a chartered accountant in India, he started out as an employee at Dairy Queen. After endless spells of unemployment and several jobs, he was able to realize his dream. Today, nearly 30 years since my parents immigrated to the US, he is a small business owner that sustains a community.

Let's Talk Social Science:

In a report published by the Brookings Institute, “Moving up: Promoting workers’ economic mobility using network analysis,” it is revealed that the nation’s labor market is full of mobility gaps and barriers. In the network model created, the labor market is described as a metaphorical city. “If we imagine the labor market as a small city on a hill, where the highest-paid occupations are located on the top floors and lowest-paid on the bottom, we see that workers’ experiences and mobility prospects are determined by where they start.”

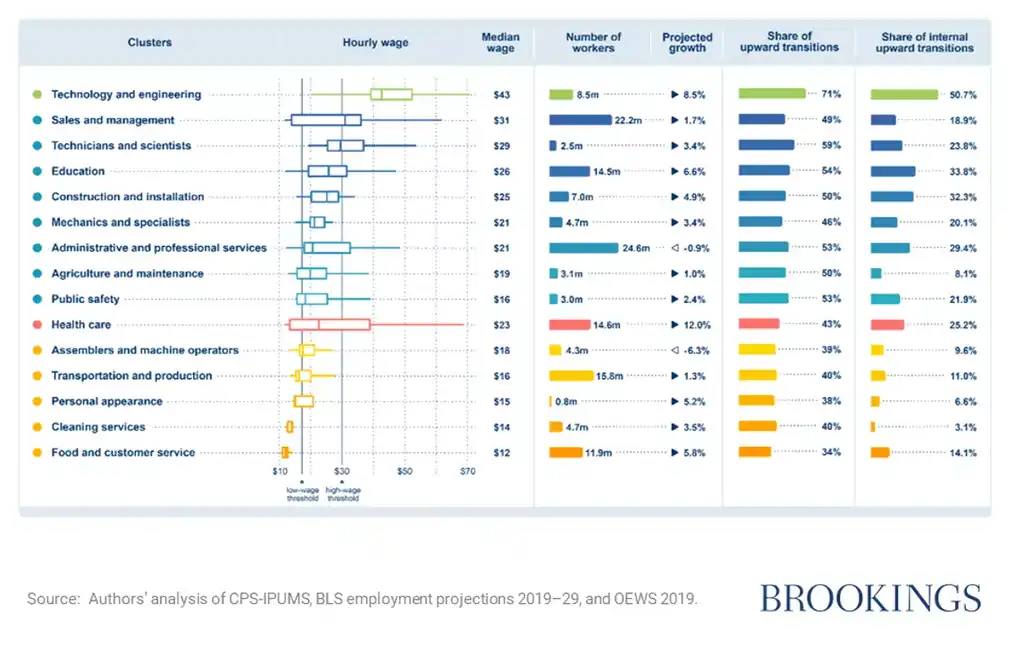

Brookings employed data on 228,000 real occupation-occupation transitions to trace the most common pathways into and out of 428 occupations across 130 industries. The Institute found that workers move in well-defined patterns in 15 distinct occupational “clusters” within which workers move frequently but rarely exit. Workers' mobility prospects are shaped by what cluster they are in. The lowest median wage cluster, hospitality, for instance, offers its workers the worst prospects for upward mobility. Out of all occupational transitions from hospitality, only 36 percent are upward. Comparatively, 66 percent in the utilities and professional services sectors are upward, two of the highest-paying and most upwardly mobile sectors.

Findings from the report suggest the following:

- Mobility gaps exist across wage level, industry, race, and gender

- Many workers in low-wage occupations get trapped

- While pathways exist, they are narrow and full of hurdles

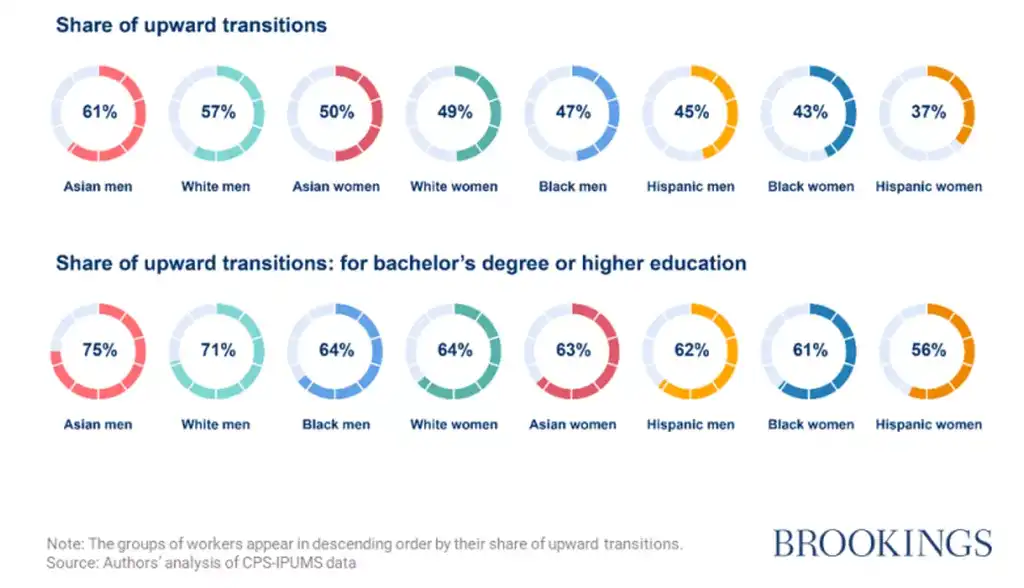

Across the labor market—irrespective of education or sector—workers do not experience mobility equally. Hispanic and Black women face the lowest shares of upward transitions overall: 37 percent and 43 percent, respectively, compared to 57 percent for white men and 61 percent for Asian men.

The gaps remain regardless of education: For Asian men with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 75 percent of transitions are upward—compared to only 56 percent for comparably educated Hispanic women. That is, even with education, Black and Hispanic workers see lower mobility than their white and Asian counterparts. Therefore, the gap in mobility is not driven by racial or gender differences in educational attainment.

Additionally, manufacturing has the most prominent racial mobility gaps, with Black and Hispanic workers seeing 14- and 18-percentage-points fewer upward transitions than their white colleagues.

The mobility prospects of workers in low-wage occupations are narrow. Over 10 years, only 43 percent of workers in low-wage occupations have left low-wage work. Their chances of moving up get smaller and smaller the longer they remain. “Every four years, the probability of escaping low-wage work shrinks by half, with the chances reaching only 1 percent in year 10.” Across the labor market, middle-wage jobs that have long served as doors between low- and high-wage occupations, are disappearing.

Some low-wage occupations are vulnerable to job displacement and technological disruption. For example, after factoring in the effects of COVID-19, the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects that the assemblers and machine operators cluster will lose as many as 301,000 jobs or a 7 percent drop.

Knowing mobility across the different clusters is important but what are the opinions of the current generations on education as pathways out of lower-wage occupational clusters. And what do their dream jobs look like?

In October 2021, YPulse - the leading authority on Gen Zs and Millennials - conducted a survey among 1,200 weekly social media users, ages 13-24, in the US. According to the Trend Report, in terms of Career & Education, 90% of Gen-Z believe the best education comes from real-world experiences, and given how much college costs, they are considering alternative pathways. Over two-thirds have begun to devalue the extrinsic as well as the intrinsic value of college education.

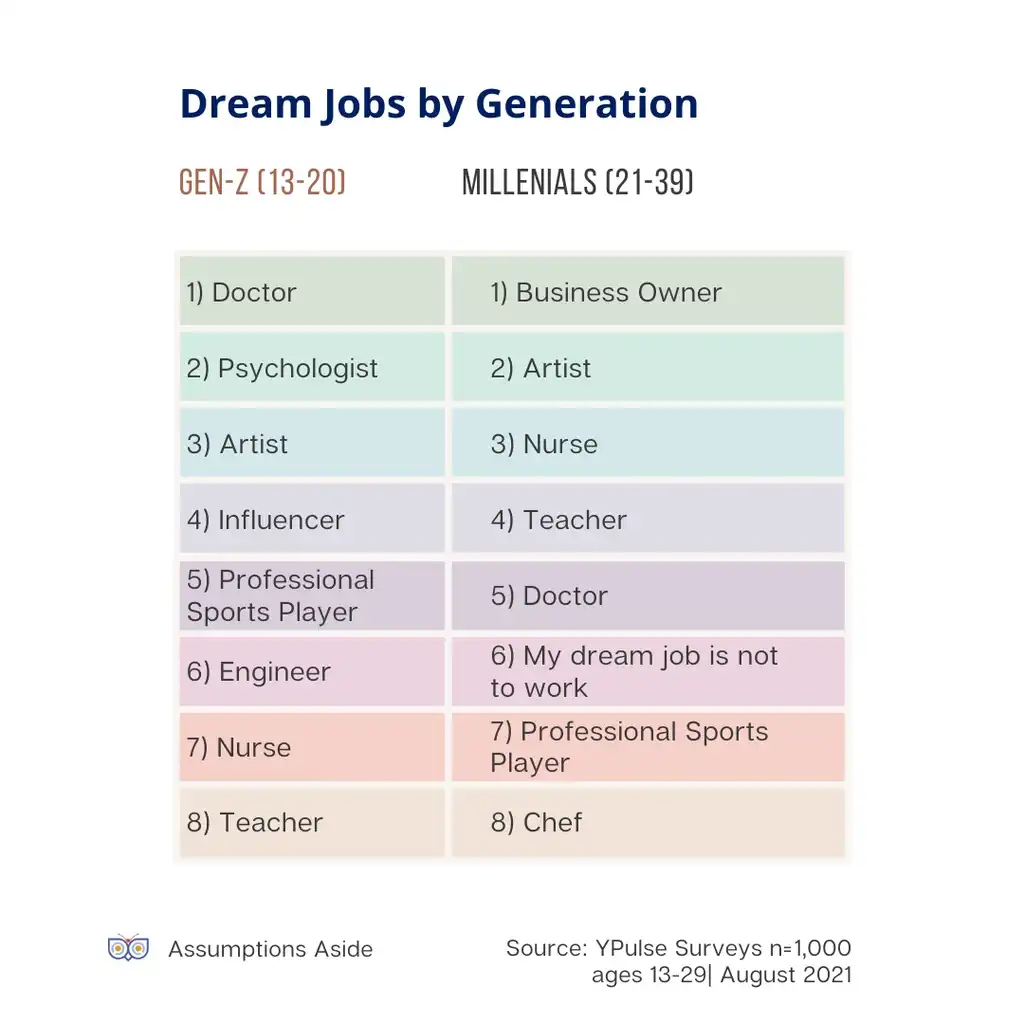

In another survey completed by YPulse on what a dream job might look like, there are some notable differences when it comes to what Gen Z and Millennials want to do.

My very niche job doesn’t show up on this list, but I’m grateful for my father who put his dreams into action and gave me the ability to choose - an option which neither of my parents had growing up. And my mother who's hard work and public health education gave my family the ticket to some version of the American Dream. Together, my parents have built a store that feeds and employs a community as well as provided critical data for behavioral risk factors for Kentucky.

References:

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2020-01/23/c_138729706.htm

Escobari, M., Seyal, I., & Contreras , C. D. Brookings Institute. Moving up: Promoting workers’ economic mobility using network analysis.

https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/instagram-trends-2022

https://www.ypulse.com/article/2021/11/01/gen-zs-dream-jobs-are-very-different-from-millennials/