A look at my path to my life’s passion; and, how everyone else gets there.

Living alone pushed me to reflect on myself and my place in society. My path through professional interests has been long and windy, starting from pre-optometry to finance and ending with economics. I began my undergraduate studies with the wish to give people the ability to see clearly because it made such a difference in my life along with my family members’ lives. After shadowing optometrists and taking core courses, I realized I wouldn’t be the right fit for the job.

I went through one field after another; I asked professionals questions, studied their daily tasks, and questioned my own interests. I had to assess my goals, education, values, skills, and interest. I was blessed to have educated parents who believed in the pursuit of knowledge. My father's chartered accounting background gave me a foundation in business, while my mother's public health and microbiology background helped me approach problems using the scientific method.

As I looked back on my path to where I ended up, I was curious how many others experienced the same experimentation. While everyone is different, many people have a similar professional path. According to Indeed, the average professional life has 5 stages: exploration, establishment, mid-career, late-career, decline. As a younger adult, I switched jobs 5 or 6 times - this was my exploration stage. As we age, we are less likely to change jobs.

Let’s Talk Social Science:

Workers change jobs to seek higher pay or a better match. Job changers with minimal joblessness move to higher-paying jobs, while those who face a prolonged period of joblessness move to lower-paying jobs and suffer persistent earnings losses (Fallick, Bruce, et al. 2021). In other words, if you have problems finding work, when you find it, it may pay less and you’re likely to keep struggling financially.

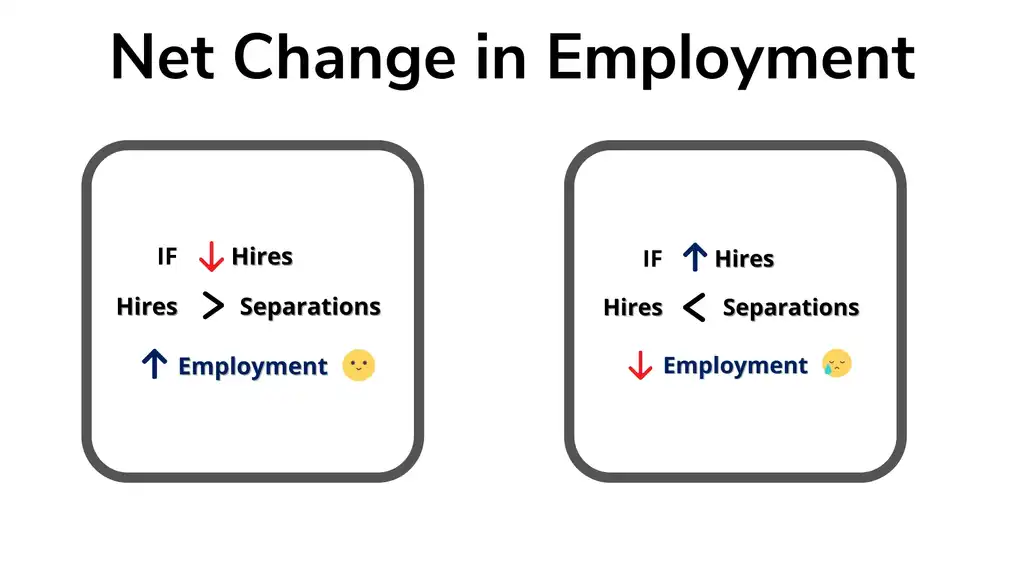

It’s not uncommon to see large numbers of hires and separations occur every month in a business cycle. The net change in employment is explained by the relationship between hires and separation (layoffs, quitting, other). When the number of hires exceeds the number of separations, employment rises even if the hires level is steady or declining (See Figure I. Below). Conversely, when the number of hires is less than the number of separations, employment declines, even if the hires level is steady or rising. For example, though from 2009 to 2019 the percent change in hires was fairly steady, we saw a net gain in employment in every 12 month period (October-September) since the number of hires exceeded the number of separations. In other words, those jobs added reports you see on some news sources can be misleading because the media typically covers only a snippet of the story. A higher number of people finding work last month might only mean that fewer were fired or quit, not that a lot more people found new jobs.

Figure I.

In a Bureau of Labor Statistics release, the following was noted, “over the 12 months ending in September 2021, hires totaled 73.3 million and separations totaled 67.7 million, yielding a net employment gain of 5.6 million. These totals include workers who may have been hired and fired or quit more than once during the year.”

Interestingly enough, the news cycle right now is highlighting the record number of people quitting and the unchanged number of job openings - 4.4 million quits (approximate supply) and job openings (demand) was little changed at 10.4 million ending in September 2021, according to the latest BLS release. The story is companies are struggling to find workers and there is a labor shortage.

The assumption when looking at these numbers is that the number of people quitting is exceeding the number of people getting hired. However, this little snippet of the story may not be the full picture. To understand the full picture we have to look at the net gain in employment as well as look at some preliminary demographics of the quits. Is a net gain in employment good or bad? Is it real or a function of people not leaving jobs for a month? To figure that out, we would have to look at the year-over-year trend.

Though the number of people quitting is at a record high, the net change in employment for 2020-2021, 12 months ending in September, is 5.6 million (as shown in Figure II. don't be afraid to click around - the chart is interactive).

According to a Harvard Business study, employees between 30 and 45 years old have had the greatest increase in resignation rates, with an average increase of more than 20% between 2020 and 2021. While turnover is typically highest among younger employees, Harvard's study found that over the last year, resignations actually decreased for workers in the 20 to 25 age range (likely due to a combination of their greater financial uncertainty and reduced demand for entry-level workers).

Figure II.

Source: Jobs Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

Circling back to my career choices, the ultimate key to finding my passion in economics began by understanding my background and roots. I noticed the variation in socioeconomic outcomes of individuals born in different zip codes in my circle of friends and acquaintances. Nobel Prize winner, James Heckman noted, “Children born into disadvantage were, very early, already at risk of dropping out of school, pregnancy, crime, and a lifetime of low-wage work.” A driving factor in my career has been identifying what led the outliers to have better health and economic outcomes because it could be applied to help others.

After graduating from LSE, I accepted a job as a Health Economist. I wanted to get experience at a firm in the intersection of academia and industry. It’s face-paced, demanding, and invests in my growth. I focus on competition economics, economic aspects of community health assessments, as well as predictive modeling in healthcare and life sciences.

I started my career search by considering being an optometrist so I could help people see more clearly.

As an economist looking at the effects of poverty and social disparities, I hope to help people see more clearly, just in a very different way.

References

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Summary,” news release (November 12, 2021), https://www.bls.gov/news.release/jolts.nr0.htm

Fallick, Bruce, et al. Job Displacement and Job Mobility: The Role of Joblessness. No. w29187. National Bureau of Economic Research, 2021.

Heckman, J. J. (2013). Giving kids a fair chance. Mit Press.